Step 1:

Hire the right designer

The biggest mistake people make when setting out to develop property is to choose the wrong designer. By designer, I mean the person who designs your extension, draws up your plans and submits and manages your planning application. Choosing the wrong one has two possible outcomes: either the council refuses planning permission and you have wasted time and money or, worse, you are granted permission for something that will be suboptimal. For a homeowner, this is an extension that disfigures your house, reduces its value, and doesn’t meet your family’s needs. For a developer, it is a development that doesn’t make best use of the site and doesn’t maximise profit.

Anyone can draw up plans and submit a planning application. There is no requirement to have basic design qualifications or competence. Most designers are not architects. But many of these “unqualified” designers are very good at their jobs – they specialise in smaller-scale proposals, design them well, are familiar with local planning policies, and have good relationships with the planners.

Others, however, are charlatans. They produce woefully poor plans that have little prospect of getting planning permission. In this chapter, I will help you distinguish between the good designers and the charlatans. Though the point of hiring a good designer is that they do the designing for you, at the end of the chapter I also explain what is meant by good design and explore some of the common mistakes people make when planning to extend their home.

How Do I Find the Perfect Designer?

The best designers for smaller-scale developments are local. They are likely to have a good understanding of the area, local council policy, and the proclivities of council planners.

Every council receives a disproportionate number of applications from well-established, local architects and designers; they have something of a relationship with the planners. This doesn’t mean that the planners do them any favours, but it does mean that those designers may be able to get the case officer on the phone to be able to talk through any problems.

All councils keep a public record of planning applications on their website. To find the designers who are active in your area, navigate to your local council’s website, click on “planning applications”, and use the search function to bring up a list of all applications decided in the last 30 days. Take some time to work through a selection of applications that appear to be similar to yours. You may notice that a small number of designers appear again and again – these are the firms to add to your shortlist.

How Do I Spot the Charlatans?

Now you have a shortlist of designers, it’s time to flush out the charlatans. There are four clues to help you separate the wheat from the chaff.

First Clue – Price

The first clue is price. You get what you pay for (most of the time, at least). Low prices are a red flag. A sum of £300 or £500 is not enough to compensate a good designer for visiting a property, providing advice, measuring the building, drawing up a full set of plans, revising them as needed, and submitting and managing the planning application. Spending small amounts on a designer is a false economy – the development will be poorly-conceived, there will be errors on the plans (that may make any planning permission you do obtain invalid), you will have no credibility with the planners, and you are much less likely to be granted permission. If permission is granted, the development may be difficult to build. You should expect to pay between £1,000 and £2,000 for a designer to prepare full, detailed planning drawings for an extension, and to submit and manage your application.

Although a low price is a good indicator of poor quality, a high price is not always a sign of excellence. I worked for a council where a majority of the applications for extensions were submitted by two architects, working for different firms, who monopolised the local market. One charged twice as much as the other (£2,000 to £3,000 for a relatively straightforward application). When applications were received from the cheaper architect, my colleagues and I barely glanced at them before recommending approval – he generally submitted thoughtful and sensible proposals that complied with local planning policies and guidance. He had great credibility and we felt bad on the rare occasion that amendments were required or an application of his was refused. When applications were received from the other, more expensive architect, my colleagues and I groaned, reached for our red pens, and began drafting our objections. His plans were poor quality and error strewn and he proposed developments that did not comply with local policies. In this example, the cheaper architect represented much better value. So, one must avoid low priced offerings, but higher prices do not necessarily signal virtue. How else can one identify the best designers?

Second Clue – Quality of Design Suggestions

The second clue is the quality of their suggestions in respect of the design of the building and their knowledge of what will and will not be granted planning permission. The charlatans will simply ask you what you want and prepare plans accordingly. If you ask them whether you might be able to get permission for a 10-metre-deep extension rising three storeys high, they will nod sagely, suck on a pencil, and say they can’t guarantee anything, but it is worth a try. If you ask them how it will be designed, they may look at you blankly and explain that it will have four walls, be built in brick, and have a tiled roof. If you ask about the internal layout or “flow” they may suggest you attach it to the end of your kitchen and access it through a door. If you express concerns about possible impact on a neighbour’s window, they will say that the neighbour is too far away to be affected. If you ask them whether the proposal complies with local planning policies, they will smile reassuringly and say that they get permission for these kinds of extensions all the time.

A good designer will do just that – design. They will ask you what you are trying to achieve, what you need the additional living space for and how you would like the house to be configured. They will have a good understanding of how your house can be altered in a way that is sensitive to its original shape and proportions, and how to make best use of space. They will almost always push back and bring some of your dreams crashing down. Most homeowners, in my experience, want more than can realistically be achieved. Only confident designers will burst their bubbles. The best will find creative ways to meet your needs or will make suggestions that hadn’t occurred to you before.

Designers need an iron will. Few homeowners ask for a simple extension that will sail through the planning process. Almost everyone wants to push the envelope. Many want an extension bigger than the largest extension on the street. Some want a combination of all the different extensions visible on other houses in their area, combined into one mega development. From the designer’s point of view, the initial meeting with a prospective client is a beauty parade; crushing the homeowner’s dreams is unlikely to result in a commission. So, beware the designer who agrees with all your suggestions and does not temper your aspirations.

Remember that the designer does not guarantee you will receive planning permission. Their commitment to you is to draw plans and submit the application. They can take no responsibility for the application being refused because planning processes are inherently uncertain. This can reduce their incentive to do a good job. They can draw up a bad scheme, knowing it will never get permission, and just tell you, when it fails, that it is the fault of capricious planners and a hostile planning system. Be very suspicious of the designer who agrees to submit whatever you ask them to. To work out whether lots of your prospective designer’s applications have been refused, search on your local council’s planning application website and try and find some of their recent applications.

Third Clue – Quality of Drawings

The third clue is the quality of their drawings. Don’t ask them to send you examples, go on to a council planning website and find one of their recent applications. I appreciate that people who have never applied for planning permission before may not be familiar with scaled drawings, but most people have an instinctive sense of quality. A designer’s plans are a kind of sales pitch – they are intended to persuade a planning case officer to grant permission. It is important that they are detailed and, well, pretty.

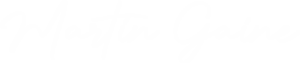

The worst plans are line drawings, like the stick men children draw, with no variation in line thickness and no shading. An example, from a case I dealt with, is shown in figure 1. It is clear, even to a layman, that these drawings lack detail and sophistication. The application was for a two-storey side extension and these drawings show the proposed front and rear elevations.

The extension doesn’t appear to have been carefully designed and the drawing does not present the extension in its best light. The drawings aren’t labelled (the front elevation is on top and the rear elevation below), and there is no scale bar. Poor quality drawings like this make it much less likely that permission will be granted and, even if it is, give you little to work from when it comes to building the extension. If permission was granted in this case, the homeowner would have been required to build the extension strictly in accordance with the plans, which may have been difficult when so little detail was incorporated. Failing to build in strict accordance with the plans leaves you open to enforcement action (see Step 6 for more on enforcement). I help hundreds of homeowners each year who inadvertently find themselves in this kind of stressful situation.

Your plans should accurately and comprehensively represent the building that has been drawn. There should be no errors. Floorplans and elevations should correspond. Differences in ground levels should be shown – if your garden is sloped, it should not appear flat on the drawing. You can’t build a flat extension on sloping land – any planning permission granted on this basis would be invalid. All plans should have proper labelling and a scale bar.

Planning drawings and construction drawings are different. Planning drawings should not show foundations or the depth of insulation. Designers who show this information either don’t understand the nature of planning drawings or are trying to make their work look more impressive to you.

Fourth Clue – Knowledge of Planning

The fourth clue is that a designer should be able to explain how they will manage the planning process and be able to clearly state what’s included in their fee. Most designers love the pure, creative process of drawing plans (that’s what they were trained for) but hate the grubby business of selling it to the planners. When quizzed, a good designer will tell you how they manage the planning application process and how they communicate with the case officer. Does the fee quoted cover include the designer’s presence at the site visit (when the case officer comes to inspect the property), for example?

It is essential that your designer is aware of local planning policies and guidance or, at the very least, is aware that taking account of local policies is critical to success, and that they will have to research them as part of the design process.

You should have a clear understanding with your designer about what happens if the case offi cer wants the plans to be amended or if the application is refused. Are additional charges levied for revisions? Will the designer meet with the case offi cer aft er a refusal to get a good understanding of what might be acceptable? Are charges levied for a second, revised application? It is crucial that the designer does not feel that they can simply walk away at the end of the process if planning permission is refused. They must be willing to continue to work with you until permission is obtained.

Do I Need an Architect (Rather Than Just a Draughtsperson/Designer)?

Though we tend to describe anyone who prepares plans and submits applications as an architect, most people preparing plans for smaller applications are draughtspeople or designers, rather than fully-fledged architects. The Architects Act 1997 states that the title “architect”is protected and it can only be used in business or practice by someone who has had the education, training, and experience needed to become an architect, and who is registered with the Architects Registration Board (ARB).

Although architects are generally the best trained in the business, they are generally more expensive than their less-qualified colleagues, and some can be just as guilty as unqualified charlatans of preparing ill-conceived applications.

Plans prepared by architects are always of a high quality. They will be accurate and look impressive; they will usually have interesting design flourishes and make good use of space. This is because architects are design-led; their weakness can be a poor understanding of planning policies and guidance, as well as of what will and will not be granted permission. Case officers are used to receiving impressive sets of plans from talented architects who have not read local policies. If I were submitting an application for a relatively straightforward extension, I would prefer a competent local designer over a talented architect with no direct experience in smaller-scale planning applications in my local area.

Should I Hire a Planning Consultant (Like You)?

Actually, though it pains me to say it, there is usually no need to pay for the services of a chartered town planner (like me). However, if you choose not to employ a planner, ensure that your designer has a good understanding of local planning policies and a sense of whether or not your proposal will be successful. Too many designers prepare applications to their client’s demands without considering whether the proposal will be granted permission. This leads to unnecessary refusals, and wasted time and effort.

Planning consultants are useful where the designer does not have specific knowledge of the way a particular council approaches planning applications. They are also useful if the proposal is especially complicated or controversial. Some designers hire me as part of the overall package they sell to the homeowner – a two-in-one service. In those circumstances, I advise on local policy and guidance, provide comments on the proposed plans, prepare a planning statement to justify the proposal, and ease the application through the planning system. Some design firms have qualified planners in-house.

Planning consultants are especially useful for applications that do not comply with local policy or guidance and where the application therefore needs to persuade the council to make an exception. We often work for clients who approach us after their designer has said something like, “you can’t have a four-metre-deep extension, the council doesn’t approve anything more than three metres.” Planning consultants help in cases like these by checking the local policies, confirming whether or not the council has been granting permission for larger extensions, and advising whether an exception to usual practice or policy might be justified. There is more on this in Step 3 on planning policies and getting applications approved.

Planning consultants are also helpful for some of the trickier areas of planning. As we will see in the next chapter, permitted development is a minefield. New permitted development rights allowing homeowners to add two extra floors to their houses (from September 2020) are difficult to understand and exploit without the expert advice of a planning consultant, for example.

Case Study: The ‘Hopeless’ Flat Conversion

In 2019, Mrs Mansour decided that she wanted to convert her three-bedroom terraced house in north London into two separate flats. It was her retirement plan

– she would live on the ground floor and earn some income by renting out the new first floor flat.

She hired a local designer, who measured up the house, prepared plans and submitted a planning application. On top of the cost of paying the designer for his time, she paid an application fee to the council of just under £500. Eight weeks later, the council informed her that the application had been refused.

Mrs Mansour contacted me for advice. I discovered that her house was in an area that the council had identified as suffering from “conversion stress” meaning that a large number of houses had been converted into flats, changing the “character”

of the area, so the council would not grant permission for any more conversions. It had a clear planning policy to that effect in its local plan (its published collection of planning polices). A review of recent decisions revealed that the council had refused

all applications for flat conversions in that area since the policy came into effect and,

in the small number of cases where applicants had appealed the decision, they had not been successful.

Mrs Mansour’s application therefore stood no chance of success and had been a waste of time. This was not necessarily the fault of the designer – he had never said that he would research local policies and similar local decisions before preparing the plans and submitting the application. However, by hiring a designer who was more familiar with local planning policies or seeking advice from a planning consultant before embarking on her project, Mrs Mansour would have saved time and money.

Form v Function

Finding the right designer is the first step, but it is not quite enough. It is important for you, the homeowner, to have a good idea of what you want and to participate effectively in the design process. Pushing your designer to submit an application for something that just won’t get consent is clearly counterproductive. You should spend some time rationalising your own thoughts about how you live in your house, what kind of extra space you need, and how it may be added without harming the appearance of the building or affecting your neighbours.

If the first big mistake homeowners make is choosing the wrong designer, the second is trying to get permission for the biggest possible extension, no matter how ugly. It is a strange impulse – why disfigure your house?

There is a classic tension in architecture between form (the size, shape and appearance of a building) and function (what it will be used for). If function is prioritised, the internal space is designed to meet the needs of the user, but the consequence can be that the outside appearance suffers. Conversely, if one focuses on creating a beautiful building on the outside, the space created internally may not work.

Most homeowners start with function. They want a certain amount, often quite a lot, of extra space. What it will look like from the outside is a secondary concern. Size matters, obviously, but big isn’t always better when it comes to householder extensions. This is, of course, where the local council planners come in. They don’t care what you are planning for the inside of your house, they are concerned about what it will look like from the outside.

At some point in the past, your house was carefully designed. Some thought was given to its size and scale, its proportions, and the choice of materials. It is likely that the elevations of your house are symmetrical and that it matches the others on the street, creating a harmonious “streetscene”. Extending your home to incorporate a large volume of extra space clearly has the potential to create harm.

Monstrous Carbuncles

In 1984, Prince Charles was horrified by a proposed extension to the National Gallery, famously describing it as, “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.” The proposal was duly scrapped. He didn’t win the wider war, though. Despite the best efforts of our planners, thousands of carbuncles appear on the faces of properties up and down the country every year. Some extensions are truly horrible, and one wonders why someone would allow their home to be spoiled in that way (and how they were able to obtain planning permission!).

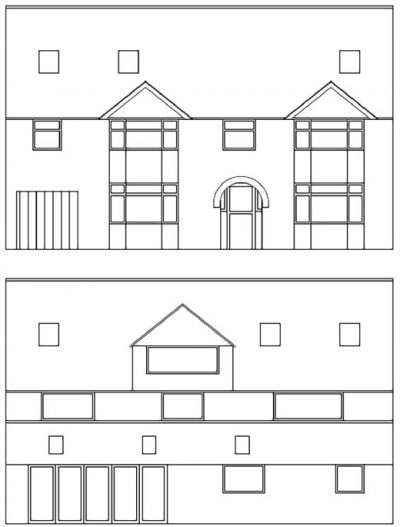

To a planner, the biggest carbuncles are those that can be seen from the street. Ugly rear extensions are much less of a problem – only a small number of misfortunate neighbours can see them. In the image in figure 2, the homeowner has achieved a very substantial increase in the size of their home by building a two-storey side extension. However, there are issues with its design. The ridge (the highest point) of the new roof reaches up to the top of the original chimney. The extension is too wide and should probably be stepped back a little from the front wall of the main house (so that it is subordinate, in the jargon). The new window does not match the windows in the original house and neither the bricks nor the tiles match those on the existing building. In this case it is likely that the homeowner obtained planning permission for a side extension but did not build it quite in accordance with the approved plans.

In the example in figure 3, a series of awkward extensions have merged two neighbouring houses, of different architectural styles, together. The house on the left has an A-shaped gable roof. The roof has been extended on either side with the addition of two dormer windows (a dormer is a roof extension; side dormers would usually be permitted development and not require planning permission), one bigger than the other. It has what might be a third dormer, further back, that extends all the way to the side wall and roof of the neighbouring house on the right. It also has a large ground and first floor side extension (the ground floor painted white and the first floor red). Only its porch extension is proportionate and well-designed.

The house on the right has also been extended – its roof was originally hipped (i.e. it had a side slope), but it was built out and a loft conversion was created. These extensions are very poorly designed (or have not really been designed at all) and though they provide acres of extra space internally, they harm the appearance of the two houses and the wider streetscene. It is hard to believe that planning permission was ever granted for these extensions – it is likely that works were carried out without permission and may be subject to enforcement action.

Size Matters

Most disputes with council planners are about size rather than siting or design. In many cases where I advise clients to amend a proposal and resubmit, I tell them to make it smaller – often substantially smaller. In most of those cases, the error that the applicant has made is to try and maximise the amount of additional space they can have, rather than truly design their extension and find a balance between form and function. Acres of unused floor space in your new breakfast room will add nothing to your family’s breakfasting experience. A smaller, more intimate space might be more enjoyable, brighter, and take less time to clean.

Living spaces have an appropriate size, determined by their function. Room sizes should be optimised, not maximised. Oversized rooms are not cosy or comfortable. There is no point in your bedroom being twice as large as it needs to be. The skills of a talented architect or designer are key here. They can create more with less and configure your house so that each room is the optimal size and the spaces are connected in a logical way, creating a natural flow through the building. Remember that building work is priced per square metre. A rear extension that is one metre deeper than necessary will cost you thousands of pounds more in building costs.

Case Study: The ‘Optimal’ Two-Metre Extension

In 2017, Mr & Mrs Paterson purchased a tired, run-down property in Leeds. It was a standard 1930s three-bedroom, semi-detached house. The couple had three children and the house was not going to be big enough for them without extensions to provide an enlarged reception space downstairs and at least one extra bedroom and bathroom upstairs.

They had a budget of £80,000, which may seem generous, but does not go very far when it comes to house renovations these days. For this, they wanted to extend to the rear at ground floor level to a depth of six metres and convert the loft with a large rear dormer window (a dormer is a square roof extension). Both of these extensions would usually be permitted development (i.e. would not need planning permission).

They came to me for advice and I referred to them to a talented local architect with whom I had worked in the past. She recommended that they limit their ground floor rear extension to a depth of two metres and convert their existing loft without adding a new dormer window. She proposed a creative internal layout that made efficient use of the space, providing a large, open-plan kitchen/diner, and a new master bedroom suite in the converted loft space. This dramatically cut the cost of the build – householder extensions are priced per square metre and smaller extensions are therefore proportionately cheaper. The Patersons were initially sceptical of the idea of a ‘miserly’ two-metre rear extension but were delighted with the final result.

Look at Your House Afresh

If you are thinking of extending or reconfiguring your home, you should start by taking a long, hard look at your house from the outside. You may not have looked at it properly since you bought it and moved in. You rush to and from it every day, spend much of your time inside it looking out, and just don’t see it anymore. It’s an invisible constant – part of your everyday.

Examine it from all angles. Cross the road and look at it from a distance. Work out what the original designer was trying to achieve – does it have original features, a certain symmetry, a particular choice and mix of materials? Examine how any existing extensions relate to the house – do they work? Do they fit in with the original architecture? Does the internal space they provide connect well with the original house? Think about how you use the house. Identify which spaces are most commonly used and which rooms or areas are almost abandoned.

Then look at your neighbours’ houses. In most English streets, the houses are similar to each other. If the streetscene is attractive and harmonious, what creates that harmony? Is it a repetition of building sizes and styles? Which neighbours have successfully extended and what makes their extensions successful?

Before approaching designers, it is good to have a clear sense of how your property was originally designed and built, what works and what doesn’t in terms of the quality of accommodation it provides, and what the wider streetscene is like. Ultimately, you want an attractive house. You need a good designer so that the extension complements the building and fits in well with the streetscene. An eyesore built onto the back or the side of your house will reduce its value and do nothing to improve your living conditions. Applying for something bigger and uglier than it needs to be sets up an almost inevitable battle with the planners, who see themselves as holding back the tide of poor design.

Battles with the planners are my bread and butter, but you can avoid them altogether by hiring the right designer and keeping your extension as small (and sensitively designed) as possible.

Step 1 Summary

- Finding the right designer is the key first step to extending your house. Local designers are often best – use your council’s planning search function to see which designers are actively submitting applications in your area.

- Be wary of designers who are either very cheap or very expensive. Do not choose the cheapest or most obliging designer – it is a false economy to scrimp on this stage of the process.

- Expect your designer to have thoughtful suggestions about how your house may be extended.

- Assess the detail and attractiveness of a sample set of the designer’s drawings.

- Quiz the designer on what local planning policies and guidance will apply to your proposal and how they will manage the planning application process.

- Curb your ambitions – size doesn’t always matter and there should be balance between the internal space created and the appearance of the extended house from the outside.

Key Questions to Ask a Prospective Designer

- What is their experience of similar applications in your area?

- Can they provide details of similar, successful, applications that they have worked on (you can look up details of these applications on the council’s planning website)?

- What local planning policies and guidance will the case officer apply when assessing the application?

- Does their fee include attendance at the site visit and any revisions to the plans that might be requested by the case officer?

- What support will they provide if the application is refused?